Get Started

The purpose of this website is to support anybody who wants to use empirical methods to explore personal questions. We call this practice “everyday science.” In the decade that we’ve been working with people doing self-tracking projects, we’ve come to appreciate the diversity of motivations, methods and tools people use to gain insight into a problem or question using their own data. We’ve also seen how certain ways of approaching a project tend to lead to success, while others increase the chance of discouragement. Here we’ve tried to collect and organize some of the most useful advice about self-tracking, with a special focus on making it easy to get started.

So: How do you get started with a self-tracking project?

You can picture your project as involving four distinct activities. Although these activities blend into each other, they do each have their own particular flavor, and by outlining them separately we think we can give you a coherent and functional recipe. The activities are: Questioning, Observing, Reasoning, and Consolidating Insight.

Questioning

The process of articulating your reasons to do a self-tracking project is crucially important, far more important than what gadget to use, what methods to apply, or what interventions to test. When you articulate your reasons, you clarify the criteria for choosing what to track and what tools to use. You also gain access to others in the QS community who may be able to help, because they share your interests.

Here is a list of some common motives for starting a self-tracking project, just to get you thinking. Do any of these express your goals?

- Increasing awareness of when or where something is happening so you can be more in control

- Learning about the frequency and intensity of a symptom such as pain, dizziness, cramps, or allergies, to support medical treatment

- Developing a skill, such as data visualization, by applying it to something you’re interested in

- Creative expression using your own data

- Tinkering with interesting hardware

- Making progress in training for sports and fitness

- Pacing physical therapy and/or recovery from injury

All of these are good reasons for starting a self-tracking project, and there are countless others. One under-appreciated motivation of tracking is that it is just a way to think more deeply about something that’s going on in your life. People have learned something of value from tracking something as simple as books they’re reading or the music they’re listening to. Not every project has to be directly focused on solving a problem. It might just be a way to organize and deepen your thinking.

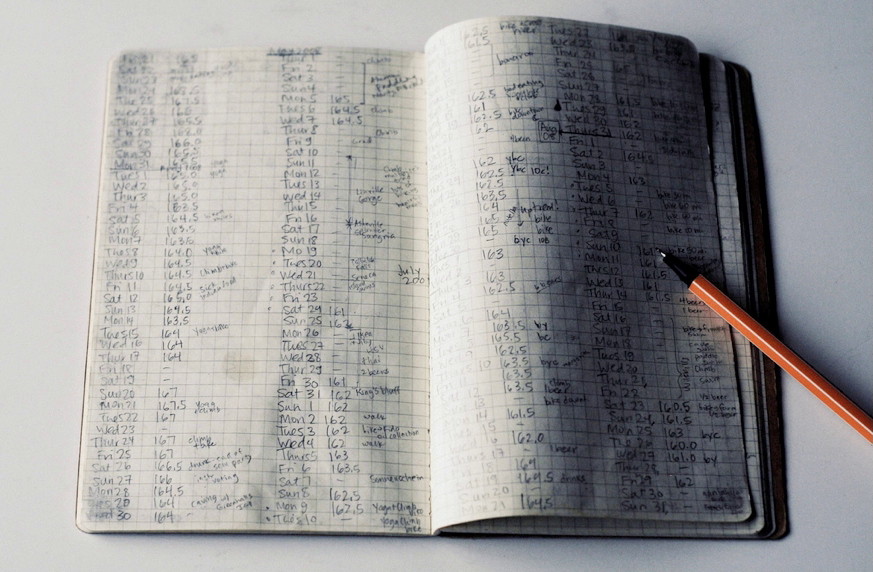

Try writing a short paragraph expressing your goals and questions. You are welcome to use the “Project Log” section on the QS Forum to post even your earliest ideas and see if others can advise. This is an easy and powerful first step: you’ve now successfully started your self-tracking project. And if it seems odd that a self-tracking project, which often involves quantitative measurement, should begin with typing or handwriting a few sentences in a notebook, keep in mind that the lab notebook has been a core tool of science since laboratories were invented.

Observing

Self-tracking projects involve deliberate observations. We know this may seem trivially obvious. But we mean something specific by “deliberate observation.” That is, that you choose one or more carefully defined elements in your life to keep track of and you isolate these elements from the stream of your experience in order to give them special attention. This involves a decision: What do you want to observe?

Deciding What To Observe

Choosing what to observe often involves some trial and error. Do some thought experiments first. Try to guess what the record of your observations will look like after your project gets going. Do you think there will be a pattern? How frequent will the measurements be? What would you be surprised to see? Even a very short planning phase of a quarter of an hour can yield important insights about what precisely you’d like track, giving you a way to think more clearly about whether the observations are likely to be relevant, convenient, and trustworthy.

- Relevant: Does the observation really offer insight into what I care about?

- Convenient: Can I collect these observations easily and consistently?

- Trustworthy: How confident am I in the measurements?

If your project involves biomedical measurements, your exploration of their trustworthiness may be more intense. We’ve offered some guidance for evaluating validity of biomedical devices used for self-tracking in this post: Is My Data Valid? However, when you are just getting started you there’s no need to wade into the challenge of doing your own validation of biometric instrumentation. You can learn a lot from tracking something simple.

Here’s an example. Jakob Eg Larson, a professor of engineering and the co-organizer of QS Copenhagen, suffered from headaches. But after he started his heading tracking project he realized it was difficult to use standard measurement approaches. After some thinking, he decided not to track his headaches, but to note each time he took his pain medicine. This was unambiguous and made his project much easier. (To find out his surprising conclusion watch his short talk: My Headaches from Tracking Headaches.)

Recording Your Observations

The material equipment for recording your observations need not be elaborate. Sometimes a smartphone and electronic sensors are useful, but there are times when a pencil and paper will do. We’ve seen many excellent self-tracking projects that involve making just one numerical measurement daily. And where the measurement is based on self-assessment, no complex technology is needed. For instance, you can record your self assessment in a notebook using a numerical scale. Examples of self-assessments we’ve seen in successful projects include:

- Mood before going to sleep or feeling of restedness upon awakening

- Interference of pain with normal daily functioning

- Subjective sense of of “readiness to train” in sports

If your project requires a lot of work every day, you’re more likely to drop it before you learn anything useful. Ask yourself: How’s this process going to feel when my initial enthusiasm dips, or my work or family life requires extra attention? We’ve been privileged to work with self-trackers doing marvelously complex and demanding projects, some involving millions of observations. But among the best projects are the simplest. For inspiration, take a look at the way designer Ellis Bartholomeus collected observations about her state of mind.

Securing Access To Your Observations

Many self-tracking projects involve tools that collect observations passively. For instance, there are wearable gadgets that track activity, sleep, location, blood pressure, body temperature and heart rate. Other projects make use of tests available from a lab or pharmacy: blood glucose, ketones, cholesterol, luteinizing hormone, and many more. When you are getting started on a self-tracking project there is one especially important question you’ll want to ask about your tool: Does it give me access to my own data? Absurd as it may sound, many self-tracking tools only offer summaries of data, or only offer data in a ridiculously inconvenient format.

Here’s health educator Ilyse Magy describing the problem of a good tool with bad access. The question of access is especially important for tools that collect data passively and store it remotely. You’ll want to test for access right at the beginning of the project. Find the export data function. Take a look at the file it sends you. Is the record of your observations available in a tabular format, so that you can open it in a spreadsheet? If not, consider whether there is an equivalent tool with better access.

For combining data from different sources so that you can access it for personal reasons, we prefer to recommend tools that are specifically focused on helping individuals without exposing them to risk, such as Zenobase, created by Eric Jain, co-organizer of the Seattle Quantified Self group. If you use Apple Health, you can take advantage of our free QS Access App, which allows you to securely access most of your Apple Health data in tabular format that you can download it and open it in a spreadsheet.

Help With Tools

There are many hundreds of commercial self-tracking tools that could be relevant to your project, along with countless everyday and DIY tools that might work even better. If you are looking for a specific tool, or have questions about a tool you’re currently using, try posting in the QS Forum. We keep an eye on questions posted there and try to get them answered.

Reasoning

Now that you have the record in hand, there are many different ways to interrogate it. If you have a numerical record, you can take advantage of centuries of accumulated knowledge on teasing meaning out of data, making predictions, and increasing your confidence in connecting causes with effects. Getting meaning from data is the ultimate “low floor/high ceiling” task: there are ways to learn that are accessible to everybody, including young children; and there are approaches that may only become rewarding after years of practice. Here are three ways to reason using your observations that can work immediately.

Create a Baseline

A baseline tells you “how things are.” By carefully observing your current situation, you set yourself up for knowing when and how it changes.

Try a one number baseline: A baseline measurement can be as simple as a single number representing a single measurement. How many pushups can you do without resting? That’s your baseline for pushups. You can sometimes use a single number baseline to represent complex phenomena. For instance, the late Seth Roberts, a highly creative experimental psychologist who helped create the culture of the Quantified Self community in its first years, gave himself a simple cognitive test every morning. He paid special attention to his “record score,” a single number that helped spark new ideas about things to test when he saw an unexpected improvement. (Today, you can set up your own quick cognitive tests using the free service by Yoni Donner called “Quantified Mind.”)

Make a baseline from an average: When you have a measurement that tends to jump around due to normal fluctuations in daily life (think about heart rate, blood pressure, body weight, or mood) you may need to take an average of multiple measurements to acquire a meaningful baseline. Thinking about how to use an average for your baseline will naturally push you to consider what you expect the variation from measurement to measurement to be, and how you expect it would change based on different conditions. For instance, is the baseline you create from morning measurements different than the one you create from evening measurements? This simple process of measuring a number of times and calculating the average leads directly to learning.

Collect a “bucket” of informal daily observations: Your method of creating a baseline will reflect what you hope to find out from your project. When you think about your baseline, go back to your question. What are you wondering about “how things are?” You can use a set of casual observations, even in the form of simple notes, as the baseline for your project. Your choice of what to note down expresses your sense of what factors you’re guessing may change over time.

In this video segment, you can see how college student Lydia Lutsyshyna uses descriptive notes about her daily activities, such as the names of the friends she saw each day, to anchor a self-tracking project that included an intervention.

Use a Timeline

Perhaps the most common formal tool for reasoning with data is a graph showing change over time. Whether you have just a handful of observations or many millions of them you can usually find a way to line them up in a row according to when they were made. Timelines can present fascinating – and frustrating – technical challenges, especially when dealing with big numbers and diverse observations gathered using different methods.

But a very easy way to make timeline is to take a sheet of paper and label the bottom with the times of your measurements; then mark the number given by your measurement at that time in the vertical column above. Then just draw a line between each of the measurements, like in a game of connect-the-dots: there’s your timeline. In the segment of the video we’ve cued up here, you’ll see a rather remarkable version of a basic timeline chart, created by Jon Cousins and presented at the London Quantified Self meeting in 2011.

Retrospective Annotation

Look at the record of your observations. Is there a change over time? What are some possible reasons for this change? In many cases, the answer to this question is not obvious. In thinking about your own data, you’ll often want to explore what else was going on during this time.

Some people set out in advance to “track everything.” We have a different suggestion. Sometimes simply using your memory to reflect on what your timeline makes visible will give you ideas about causes and effects. Also, in this age of digital tools, many of the things going on in our lives create a record we can consult after the fact. Most digital photos contain a time stamp, allowing you to go back to the day of a measurement and get hints about what you may have been doing that day. If you use a digital calendar, then you will know what appointments you had. Your email also contains many details that can help you reconstruct your past. It’s often possible to annotate our observations retrospectively by going back and adding contextual descriptions to interesting moments.

When you are reasoning about your own data, consider all the digital traces you might consult. The scholar Shoshana Zuboff has described the current era as “the age of surveillance capitalism,” describing how a few powerful corporations use the digital records of our lives to monopolize power. Here, we’re proposing an alternate use for our passively collected digital traces; that is, to help us privately and personally figure something out for ourselves.

Consolidating Insight

A self-tracking project is a continuous learning process, and every step, from the first moment of thinking about what questions you want to explore, offers a chance for finding something out that can be useful. However, there’s a specific activity that comes with the development of a project that support creativity and focus in thinking about your own data; that is, acting on and sharing what you know. In making decisions based on what you learned, and in describing what you’ve learned to others, you’ll often find yourself revisiting every step of the process, thinking more deeply about it, and even trying out new techniques to test and illustrate your ideas.

Again and again we’ve seen that sharing the details of a project – something that may look like a final step – is actually a way to learn more. There are many ways and places to share your project. You can present a Show&Tell talk at a local QS meetup or Quantified Self Conference. You can write a blog post about it and post the link to twitter with the #quantifiedself hashtag so others can find it. Or you can write about it in the QS forum. Here are some practical tips for sharing your project.

“What Did You Do? How Did You Do It? What Did You Learn?”

These three questions are the structure of a Quantified Self Show&Tell talk. Don’t skimp on the “how.” A careful discussion of your tools and methods may be more important than the results of your project, containing seeds of new questions and ideas. And when you prepare to share your project, give some fresh thought to what you gained from doing it. We’ve seen many projects where the most useful analysis doesn’t occur until the presenter is preparing their talk! The fact that others will be listening creates a useful push toward coherence and consolidation of insight.

Be an honest reporter

We learn best from honest accounting of experience. Even (and especially) when sharing with an audience of experts, there’s no need to make your results more impressive than they actually were. Things that don’t quite work can be as revealing as things that do. In an age of hype and alternative facts, it’s refreshing to hear about ideas in progress whose import is still being explored.

Resist the urge to generalize

Just because you experienced a result, doesn’t mean others will. In sharing self-tracking projects, your particular experiences are more valuable than broad conclusions and discoveries. A self-tracking project doesn’t typically aim to uncover a universal fact about human experience, or the norm for a group. Instead, it’s just one case. Our individual reports are valuable and instructive on their own terms, because they show what’s possible.

Value good questions and stay in touch

Finding good questions is important. It’s where this guide began, and it’s where it ends. If your self-tracking project suggests good questions to others, you’ve given them valuable assistance; and if their questions inspire you to look again at your observations, they’ve reciprocated with something that can have great value to you. We hope we’ve encouraged you to think about what questions you have in your own life that might be tractable with empirical approaches. There is no single right way to begin. You don’t need to impress anybody or get anybody’s approval. But we do hope you’ll share what you learn with us!