First QS Masters Thesis: Part 2!

Adam Butterfield

May 29, 2012

After a year of research and writing, I’m finally finished with what could be called the “first master’s thesis on Quantified Self.” If some of you didn’t catch my first post, you can find it here. I spent about a year conducting research on Quantified Self for an MA in Applied Anthropology at San Jose State University. Technically, I didn’t write a “thesis” but a “project report,” because I conducted an applied research project on QS Meetup groups rather than “thesis” type research. To fulfill the requirements for the MA I had to produce two reports. The first was a report containing the findings from the research on the meetups, which I presented to QS Labs (see the earlier post). The second was a project report, which is the document I submitted to my department (which I would like to present here). For the most part, the purpose of the project report is to document the research process, including methods and theory. In addition to that, I was able to fit in some general info about QS and self-tracking into my report. Section one and section four will probably be the most interesting to members of the greater QS community. The following is an excerpt from section four.

You can see the full report here.

The practice of self-tracking

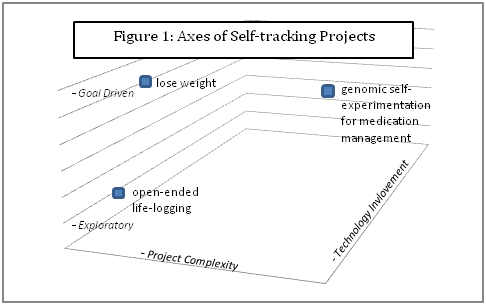

The range of self-tracking projects that people take on is diverse and tracking can focus on almost any aspect of life. Grouping by domain, such as sleep or weight, is one way to describe self-tracking practices. However through my research, I identified three axes that can be used to describe or locate self-tracking projects within the spectrum of these phenomena. Figure 1 (below) represents the three axes as a three-dimensional field, with sample self-tracking projects plotted as examples of how projects configure within this space.

The first axis is the degree of technological involvement. Self-tracking projects can heavily rely on complex devices with advanced sensors or on sophisticated laboratory tests. In other cases, self-trackers may use only a pencil and paper. The technology axis is essentially the initial line that delimits what can or cannot be tracked. In order to monitor and record data, you need certain sensors and recording devices. In some cases, self-tracking projects are driven by the technology; because there are sensors and devices to take measurements, people are using these technologies to monitor and collect data. In other cases, the self serves as both the sensor and the recording device.

The second axis is the level of complexity in the design of the self-tracking project. On the more complex side are projects often referred to as “self-experiments.” Self-experiments usually employ the scientific method to some degree, collecting baseline data, testing hypotheses, and in some cases controlling for variables. Some self-trackers try to find correlations across data sets, for example, trying to figure out what factors affect their sleep quality, by monitoring and recording data on sleep quality, and correlating that data on their activity before bed or even ambient data such as room temperature at night. On the less complex side of project design are practices like “life-logging.” There is a range of different practices people will call life-logging, but one example of a simpler form in terms of project design, would be basic journaling. A practice such as keeping a dream journal is considered self-tracking, in that it produces knowledge about the self through recording information, even though the data are not numerical.

The third axis self-tracking projects can be plotted on is the extent to which projects are explicitly goal driven or exploratory. Some self-trackers have particular goals when starting a project, like wanting to lose weight or improve sleep. Other self-trackers collect data with the intention that they will be able to do something with the data in the future (what that something is, may or may not be known), or in some cases track things just to keep track of them. Examples of this last case are things such as tracking daily step count with a pedometer or using mobile phone applications to “check in” to places you visit each day simply to have a record of that.

Self-tracking projects can configure onto these axes in almost any way imaginable. The categories on each of these axes are also negotiable. Different people may not agree what constitutes a high or low level of technology involvement. In some cases, someone might not even consider things like pencils and paper technologies. Similarly with practices such as journaling, some might argue the extent to which journaling would be considered life-logging or even self-tracking. There are also secondary factors that can help classify a project, such the length of a project, whether the project is an intervention or data collected to inform an intervention, and whether the data collected is primarily objective/collected by passive sensors, or subjective/based on self-assessment.