Fitbit vs. Moves: An Exploration of Phone and Wearable Data

Ernesto Ramirez

February 12, 2015

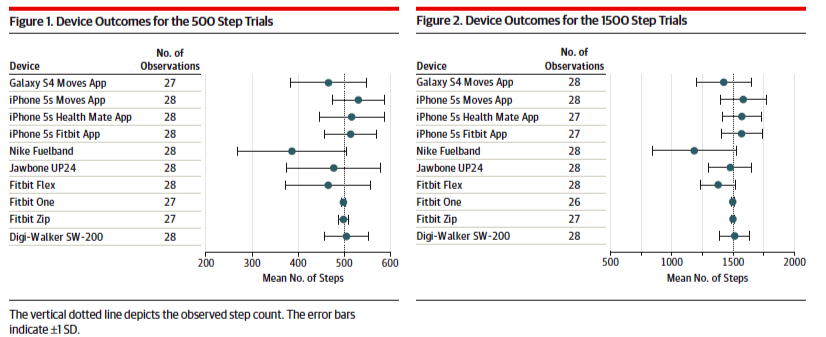

Like many people paying attention to the press around Quantified Self, self-tracking, and wearable technology I was intrigued by the many articles that focused on a newly published research letter in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The letter, Accuracy of Smartphone Applications and Wearable Devices for Tracking Physical Activity Data, authored by Meredith A. Case et al., described a laboratory study that examined a few different smartphone applications and self-tracking devices. Specifically, they tested the accuracy of steps reported by the three different apps: Moves (Galaxy S4 and iPhone 5s), Withings Health Mate (iPhone 5s), and the Fitbit app (iPhone 5s), three wrist-worn devices: Nike Fuelband, Fitbit Flex, and the Jawbone UP24, and three waist-worn devices: Fitbit One, Fitbit Zip, and the Digi-Walker SW-200. Participants walked on a treadmill at 3.0 MPH for trials of 500 steps and 1500 steps while a research assistant manually counted the actual steps taken. Here’s what they found:

As the data from this research isn’t available we’re left to rely on the authors description of the data. They state that differences in observed vs device recorded steps counts “ranged from−0.3% to 1.0% for the pedometer and accelerometers [waist], −22.7%to −1.5% for the wearable devices [wrist], and −6.7% to 6.2% for smartphone applications [phone apps].” Overall the authors concluded that devices and smartphone apps were generally accurate for measuring steps. However, much of the press around this study dipped into the realm of sensationalism or attention grabbing headlines, for instance: Science Says FitBit Is a Joke.

Part of our work here at Quantified Self Labs is to encourage and help individuals make sense of their own data. After reading this research letter, or one of the many articles which covered it, you might be asking yourself, “I wonder if my device is accurate?” or “Should I be using a step tracking device or just my phone?” In the interest of helping people make sense of their data so that they can come to their own conclusions I decided to do a quick analysis of my own personal data.

For this analysis I examined the step data derived from my Fibit One and the Moves app I have installed on my iPhone 5. (Important note: the iPhone 5 does not have the M7 or M8 chip present on the 5s and 6/6+, respectively, which natively tracks steps.) I had a sneaking suspicion that my data experience differed from the findings of Case and her colleagues. Specifically, I had a hypothesis that the data from every day tracking via the Moves app would be significantly different than data from my Fitbit One.

Methods

First, I downloaded and exported my daily aggregate Fitbit data for 2014 using our Google Spreadsheets Fitbit script. I then exported my complete Moves app data via their online web portal. To create a daily aggregate step value from my Moves data I collapsed all activities in the summary_2014.csv file for each day. (Side note: We’ll be publishing a series of how-to’s for doing simple data transformations like this soon). This allowed me to create a file with daily aggregate step data from both Moves and my Fitbit for each day of 2014. Unfortunately I did not have my Fitbit for the first few weeks of 2014 so the data represents steps counts for 342 days (1/24/14 to 12/31/14).

Results

I found that my Fitbit One consistently reports a higher number of total steps per day than my Moves app. Overall, for the 342 days I had 689,192 more steps reported by Fitbit than by the Moves app. The descriptive information is included in the table below:

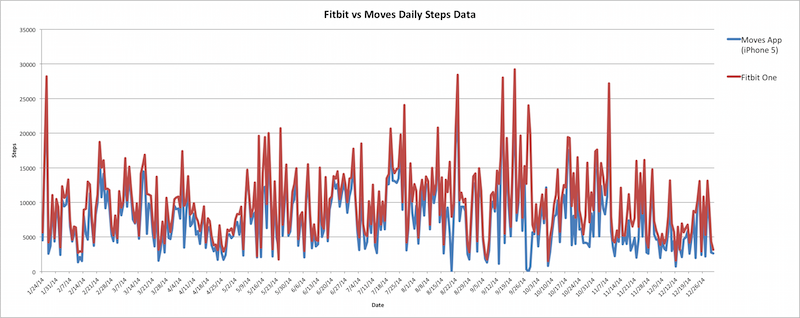

Another way to look at this is by visualizing both data sets across the full time-frame:

There a few interesting things to point out in this dataset. On two days I have 0 steps reported from my Moves app. One day, Moves was unable to connect with their online service due to me being in an area with little to no cell signal. On the other day my phone was off, probably due to an iOS 8 release and having to reboot my phone a few times.

It is also clear to me that differences in data are related to how I wear my Fitbit and use my phone. For my Fitbit, it is basically on my hip from the time I wake up until the time I go to bed each night. However, my phone isn’t always “on my body” throughout the day. I think this is probably the case for more people.

Since I wear my Fitbit at all times some of the data it captures erroneously is included in the total step count. For instance, for the last few months in this data set I was commuting about 10 miles per day during the week by bike. This data is accurately captured as cycling by Moves, but captured as steps by my Fitbit. Therefore some over-reporting by Fitbit is present in the data.

Conclusion

For my own data I found that the Fitbit reports higher steps on most, if not all days, than the Moves app on my iPhone 5. There are a few caveats with this data and analysis that are worth mentioning. First, this exploration was intended to begin a conversation around the real-world use of activity monitoring apps and devices, and the data they collect. It was not intended as a statement on truth or validity (however I would welcome the help of a volunteer to follow me around with a manual clicker counting all my steps). Second, this analysis was undertaken in part to help you understand that scientists of all types, be it citizen or academic, have the ability to work with their own data in order to come to their own conclusions about what works or doesn’t work for them. Lastly, this analysis was completed very quickly and I am sure that other individuals may have different ideas about how to explore and analyze the data. For this reason I’m posting the daily aggregate values in a open Google Spreadsheet here.

If you’re inspired to analyze your own data in this way we’d love to hear from you. Reach out on twitter or send us an email. We’re listening.