How to experiment: Guidelines from Stewart Friedman's "Be a Better Leader, Have a Richer Life"

Matthew Cornell

January 28, 2011

- Curiosity: An emotion related to natural inquisitive behavior such as exploration, investigation, and learning.

- Exploration: To travel for the purpose of discovery.

- Discovery: A productive insight.

I’ve been thinking of this triumvirate as essential characteristics of scientific inquiry – get curious about something, try out some different things to dig into it, see what you learn, and repeat. My personal interest in this, in addition to the tools and sites we share here on QS, is to figure out how specifically we navigate the process of curiosity, exploration, and discovery.

Taking a cue from Alex’s summary of How To Measure Anything, Even Intangibles, I want to share an impressive work called “Be a Better Leader, Have a Richer Life” by Stewart Friedman (see below [1] for where to find it). I’ll focus on the experimental aspects of his work and pull out some highlights related to process.

Friedman describes a four-step process, where each step relates to his four general domains of life – work, home, community, and self:

- Reflect

- Brainstorm possibilities

- Choose experiments

- Measure progress

The first step, reflect, is where you think about your priorities in each of those four domains and compare them to how you actually allocate your time and energy. This will identify conflicts that should guide your choices of where to start experimenting. (I think of this kind of goal-driven approach as “top down” experimenting, as distinguished from “bottom up” where you start from an observation that catches your attention, such as when I noticed I am moodier after drinking alcohol, and start self-experimenting from there.)

In step two you brainstorm possible experiments that will close the gaps identified in step one and bring you more satisfaction in life. The author stresses the importance of putting together a long list of small experiments. The author notes that keeping them small helps minimize risk and gets results quickly. I especially like his guideline that the most useful experiments feel like a bit of a stretch: not too easy and not too intimidating.

The third step is to choose which of the candidate experiments to perform, i.e., which are most promising and will improve your fulfillment and performance in his four dimensions of life. I liked his suggestion that the experiments be ones that would have a high cost of regret and missed opportunities if you didn’t do them. He goes on to say that it’s not practical to try out more than three experiments at once. Not only do experiments take effort, but in Friedman’s experience two turn out to be relatively successful and one “goes haywire.”

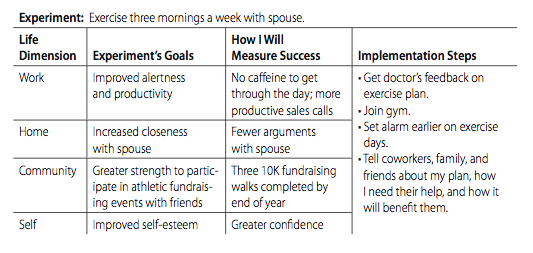

The final step is to measure progress. He has you develop a scorecard for each chosen experiment where you specify its life dimension, your goals for it, and how you’ll measure success. Metrics may be objective or subjective, qualitative or quantitative, reported by you or others, and frequently or intermittently observed. He gives sample ones like cost savings from reduced travel, number of e-mail misunderstandings averted, degree of satisfaction with family time, and hours spent volunteering at a teen center. Friedman stresses the common wisdom that, like a scientist, the only way to fail with an experiment is to fail to learn from it, and metrics help ensure that doesn’t happen. They give you hard data to analyze, and can teach you how to make better ones in the future.

Here’s a sample experiment, courtesy of the BNET article below:

Exercise three mornings a week with spouse.

Friedman gives plenty of advice beyond the four steps. In particular I like his description of the overall experimental approach:

“…systematically designing and implementing carefully crafted experiments – doing something new for a short period to see how it affects all four domains. If an experiment doesn’t work out, you stop or adjust, and little is lost. If it does work out, it’s a small win; over time these add up so that your overall efforts are focused increasingly on what and who matter most. Either way, you learn more about how to lead in all parts of your life .”

Finally, I love how he describes the value of the experimental mindset. One example is how framing an experiment as a trial can open doors that would otherwise be closed. Saying “Let’s just try this. If it doesn’t work, we’ll go back to the old way or try something different” lowers resistance because the change seems less threatening. This is valuable because it’s our nature to fear change. In fact my wife and I regularly use this with each other, such as when, during a kitchen remodeling when she got me to accept trying a vintage sink that initially, well, made me a little queasy. She pointed out that “It’s just a little experiment” and that it was relatively reversible (standard plumbing placement meant a different one could be easily installed). The result: It worked out fine. In my case I suggested we experiment with a couch in the kitchen, an idea she despised but came to love. Give it a try!

Overall, I highly recommend Friedman’s work. His book is my next read.

Resources

- [1] You can find a preview of the original April 2008 Harvard Business Review essay at Be a Better Leader, Have a Richer Life, with a short summary on BNET. He has expanded the work into a book, “Total Leadership: Be a Better Leader, Have a Richer Life” (home page, Google Books, Amazon).

(Matt is a terminally-curious ex-NASA engineer and avid self-experimenter. His projects include developing the Think, Try, Learn philosophy, creating the Edison experimenter’s journal, and writing at his blog, The Experiment-Driven Life. Give him a holler at matt@matthewcornell.org)