Mapping the Complexity of Your Own Language

Kevin Kelly

October 26, 2007

Steven Johnson, author of “The Ghost Map” and “Everything Bad is Good for You”, is the best textual naturalist I know. He has a remarkable talent for parsing literary forms in a fresh way. He was the first person to bring to my attention the sophisicated literary structure holding together modern TV serial dramas such as Lost. The other day he employed an obscure function available on Amazon to plot the textual complexity of his own books and the books of his writing heros.

Amazon examines its digital archive of several hundred thousand scanned books to extracts what it calls Statistically Improbable Phrases (SIPs). This process compares the sentences in each book to the millions of sentences in the rest of the library to find distinctive and improbable phrases. Rare sequences of words inhabiting the same few books suggest these works share more than that phrase. For instance, one of my books (“Out Of Control“) employs the phrase “perpetual novelty” more than once. That word-pair shows up in 22 other books. When I click on those references I am brought to the exact place in each these books where that passage occurs. I can quickly see the relevance (or not) of these works. Amazon highlights two dozen other improbable phrases in my book; each one leads to another cluster of related works that I was unaware of. Clearly this helps Amazon to sell more books (“If you like this one, you’ll like these.”) But it is also a new way of knowing. Once text is digital, books seep into each other’s binding to create the wisdom of the library. Books know about each other. And they carry links between books and what people say about them. The collective intelligence of a library allows us to see things we can’t see in a single book.

Another parser Amazon offers is Text Stats. It takes the digital version of the book, counts up the number of words, the number of sentences, and the number of sylables to determine several complexity ratings for that text. Either of these metrics, and others such as a concordance, are available for any book that Amazon has scanned. Scanned books are indicated by a “Search Inside” badge over the cover of the book. Text Stats are located in the Inside This Book section which is usually below the Product Details (publisher, price, copyright, etc.) section on the book’s page.

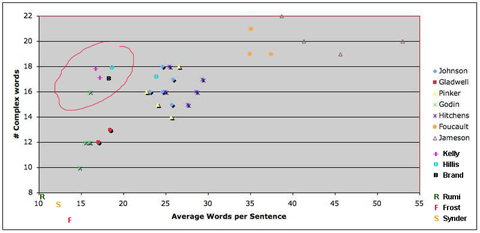

Steven Johnson spent a few hours extracting text stat data for his published books. Then he added “a few other authors that I assembled in an entirely unscientific fashion: Malcolm Gladwell, Steven Pinker, Seth Godin, Christopher Hitchens — and then, just to see how far I’d come, I threw in my intellectual (and, sadly, stylistic) heroes from my early twenties, the post-structuralist legends Michel Foucault and Frederic Jameson.” When he plotted the average number of words per sentence verses the complexity of words — which as far as I can tell from Amazon is roughly how many big words you use — he produced a graph charting the relative complexity of an author’s language.

The results are instructive and visible in his chart reproduced below. Johnson and the other popular non-fiction writers he admires form a cluster. He adds after “eyeballing” the stats of other serious science writers such as E.O. Wilson, Dawkins, Michael Pollan, they also fall in this cluster. My own quick troll through Amazon Text Stats also yield the same data. The most popular non-fiction writers have an average sentence of 22-26 words, and a complexity rank between 14 and 18.

There are some notable exceptions. Both of Malcom Gladwell’s perennially bestselling books are significantly lower in sentence and word complexity, as are Seth Godin’s perennially bestselling books. On the other hand, Johnson’s youthful literary heros are in a distant country simplicity-wise.

Check out Foucault and Jameson. They are literally on another planet. The top spot goes to Jameson’s “Postmodernism” book which I read like scripture my first year of grad school: 53 words per sentence!

I was curious to see where my own books landed, so I copied their text stats from Amazon. While I was at it, I also extracted the metrics for two of my friends and mentors whose writing I love: Stewart Brand and Danny Hillis. I was very surprised to find that the three of us (and one of Seth Godin’s books) formed a new cluster off to the side of the power curve (circled below in red).

I am not sure what to call this diversion, but according to Amazon, my sentence length is even shorter than one of Gladwell’s book! And this shortness was maintained during the entire 210,000 words in Out of Control. One of the things that Steven noticed about this unscientific sample is that there is a remarkable consistency in language within an author’s work, despite varying subjects, forms, and book lengths. And this was true of my own. I had guessed my very short, less complex book, “New Rules for the New Economy”, would have a shorter average sentence structure than the heavy, long, complex Out of Control, but no — it had the same 17 words per sentence. Also note that the Danny Hillis book in this circle is The Connection Machine — his doctoral thesis explaining how to build a massively parallel supercomputer.

If we can believe the stats, the style of this group (which I am sure is inhabited by many other writers) is marked by short sentences using big words. We might call it “telegraphic depth.” Perhaps it is derived from a journalistic approach?

UPDATE: Reader Michael Nielsen wrote in to say: ” The Kelly-Brand-Hills cluster is located at the same place as the standard textbook on quantum computing! This is the book “Quantum Computation and Quantum Information“, by myself and Ike Chuang of MIT. It’s a 700 page postgraduate text. It has a sentence length of 16.9, and 19% complex words, so it sits at the top of the cluster. Some browsing around shows that these stats are not unusual for postgraduate books in the physical sciences.”

So now that I think of it, “telegraphic depth” is exactly what you want to find in a graduate level textbook.

I went hunting for more extreme short sentences and big words and in my search sent me to the poets. But I did not find telegraphic depth in poetry. Much to my surprise, poets are literally off the charts in simplicity. I charted a single book of Rumi (Coleman Barks translation), Robert Frost and the modern Gary Snyder, and found that they use single digit simple words, and very short sentences. (They really are off the chart, below the line in the lower left corner.) Yet, their work is complex. So no one should knock simple sentences.

I agree with Steven that there should be a league of amateur text mappers who take advantage of these new stats, in the way of fantasy baseball. The insights you can mine from the text is just one of the fruits of a universal library. At the very least, it’s a metric than all writers should know about their own work. Where’s the tool for bloggers?

(When I pointed out my chart to Stewart Brand he wrote back: “Amazing!!! Nice work. Sorry:

Astonishing!!! Admirable exertion.”)