Recovering from ACL Surgery

Davis Masten

January 27, 2022

ACL Surgery Recovery is painful and the stakes are high. My recovery process would have consequences I’d live with permanently. My surgeon had done surgery only twice before on a person over 70. He typically did not recommend it because of the risks, demands and pain involved over months of physical therapy.

On the other hand, I’m experienced at recovering from sports injuries. I had 7 concussions by sophomore year in college. Ten years ago I was read my last rites after a surfing accident. I’ve learned I’m psychologically resilient, and that being engaged and creative during the recovery process can help you beat the odds. So I went ahead. I had the surgery.

It’s now eight months later, and I’m certain I made the right decision. From this end of the experience, I can look back and see the effects of certain choices I made about how to approach the challenge, and I want to share what I learned from using integrative approach, including a strong element of personal science.

First, I gave some thought to my highest level goals. They were:

- Be stronger and healthier than before my skiing accident.

- Don’t overdo it and cause a setback.

Next, I thought carefully about what to track, taking advantage of the practical advice about personal science that I’ve found in the Quantified Self community. I decided to keep simple daily log with a record structured like this:

- Focus for the day

- How does today compare to the day before

- The day’s key issue

- Anecdotes

I used a numerical rating for the comparison of today with yesterday, with 1 meaning worse, 2 meaning equal, and 3 meaning better. I limited myself to three anecdotes per day.

These self-assessments represented my foreground phenomena. They were the factors I was paying the most conscious attention to, that I was most curious about, and that I wanted to see improve.

In addition, I used data from my Apple watch Series 6, my Oura ring, my Calm app, and the clinical data from my care team. These represented my background phenomena, data that I might use to understand more deeply what was affecting my improvement and the issues I was facing.

Once I organized my Personal Science approach, I went to the various teams of professionals at Barton Hospital, in Lake Tahoe, where the operation and recovery would be managed: surgical team, internist, fitness coaches and physical therapists. All four teams were encouraging. In these pre-surgery conversations, I was told that the stronger I went into surgery, the more likely I would have a quick recovery. So I did the recommended workouts, trying hard to be ready.

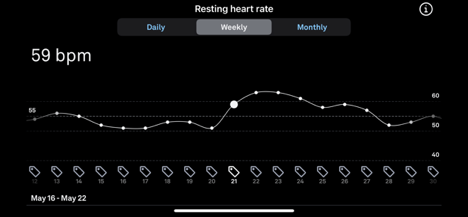

Surgery was on May 18. My average Resting Heart Rate (RHR) that night was 53. My RHR spiked right after the surgery and was highest in the first two weeks. Up 28%. Also, I was miserable from pain, weakness and inactivity. My RHR did not drop back down to 53 for the first time until June 28. It was not consistently in the 50s until July. My struggles are unambiguously illustrated in the graph above.

In the first two weeks after surgery, there were seven days where I felt worse than the day before and seven days where I was about the same. There were zero days when I felt better. This is not to say that I did not improve. Clearly the wounds were healing. But recovery can be complicated; the healing process itself felt very bad.

Postoperative hypoxemia

On the day of the operation I spent 4 extra hours in recovery while my blood oxygen levels went back up and stabilized. That night, my Apple watch showed blood oxygen readings in the 90+%. Three days later I wrote “wheezy, shallow, high pitched sounds”, and my blood oxygen levels ranged from 76-97%. The next day “more wheezes” oxygen 78-93%. My blood oxygen did not start to have consistent readings in the 90s for more than two weeks after the operation. Postoperative hypoxemia, or low blood oxygen level, is a known risk of surgery. Maybe it was the lingering effects of anesthesia, maybe the 6,100’ elevation, maybe the opioid painkillers; whatever the cause, I had it.

On the fourth day of my recovery I stretched the opioids out to every five and a half hours instead of the prescribed four. My notes record me attempting to manage the tradeoff between “Oxy feeling” and “pain.” I did not like this drug. Seven days after the surgery, my physical therapist mentioned to me that my thinking was fuzzy. I went to the surgeon’s team and asked if I could be taken off the Oxy and, instead, try medical marijuana. They approved the plan. My brain fog cleared overnight.

The surgeon had me in physical therapy the day after the surgery. Although I felt horrible overall, my knee was making progress. A key metric is “flexion.” That is, how much you can bend your knee. To measure flexion, you lie face down on a table and somebody lifts up on your ankle until you scream. On the third day after surgery, I got to 90°. But for full recovery the ankle has to be pressed all the way up into your buttocks, reaching 120°. This seemed like a long way. But the physical therapist told me that 90° was very good for right after surgery, and he thought my pre surgery exercises were paying off. I watched this number carefully. I reached 95° six days after surgery, 115° in week 3 and 120° at week 4. This was uplifting progress, and good to see, especially when I wasn’t feeling well overall.

I found it very useful to set a focus daily. My focus on the majority of days was either “reduce swelling” or “ice and elevate.” How much focus does it take to ice a knee? A lot, because I had to do it every three hours. Along with wearing compression socks. Sleeping with a pillow between my legs. Trying not to limp with crutches. Trying not to limp without crutches. Trying not to limp with a brace. Trying not to limp without a brace. Focus! Keeping this record of what I was working on daily kept me engaged when often I just wanted to retreat.

On the tenth day I started my limited upper body workouts. At first, I did these workouts sitting down. I was not comfortable. Distractions became increasingly useful to keep the pain out of my mind. I had to set intentions to keep busy: keeping my logs, singing, song writing, photo processing and ukulele playing were ways to cope. Eventually, on week three, I could take my first walk outdoors, and ride a stationary bike for five minutes. Because the ACL tear was on my left leg, I was able to drive, and I took my first trip on my own in the car during week four. I ran a few errands, then came back and took two involuntary naps. My leg was still very sore, twitches and pains were on going as the muscles reconnected and the neurons fired. I tried a variety of things to maintain my mental health, including meditation and conscious breathing.

Unexpected sadness

With the surgeon’s permission, I went to San Francisco to be an usher in a memorial service for a friend at Grace Cathedral. There, I felt crushing sadness. Along with the emotions, came pain. I had no ice, and on the six days surrounding the travel, I felt worse on five. Was I slipping into depression? But, looking at my log, I could see that even as my days seemed to be getting worse, my resting heart rate was improving. It helped to have this data to encourage me.

After a month, I no longer needed to wear my brace except when someone might hit me. And they let me do exercises standing up, very carefully. I even got to walk downstairs, one foot in front of the other. Scary! My incisions started hurting as the rest of my leg and body got more exercise. But my log showed my progress.

During week six I walked 10,000 steps for the first time, kayaked for 20 minutes and played ukulele. I felt like my recovery might be accelerating. But then my sister in law of 55 years died in South Carolina. I had to be there with my brother. Throughout this trip, my resting heart rate continued to improve even though my subjective experience was worse day after day. I was glad I went to South Carolina but I paid a price.

Acceleration

When I came back I found out that the acceleration of my recovery was real. Two days after my return, I walked 5 miles and kayaked for 40 minutes. As the summer went by, I found myself in the third month since the surgery. During week nine, I had six worse days, six days about the same and ten days better. I was steadily improving at last. Certain that I would be ok, I decided I no longer needed my personal science log.

Although my recovery was not over, and I still had many months ahead, I decided to ask my physical therapist to assess my progress in comparison with others who have had the same surgery. He said there is a range of outcomes: some go very well. Some do not. I am clearly on the very well side. He added that my pace of recovery would be still be considered good even if I were 35 instead of 70.

A big benefit of my personal science project is that it made me feel more engaged in my recovery. The medical team liked that I was thinking and planning from the beginning. Taking notes every day helped me be more aware what was going on, taught me that the issues of today were not necessarily going to be the issues of the next day.

I also benefited from noticing my progress. And as I tried to score the day or add anecdotes, I could put my feelings and symptoms in context. Generally I was getting better as I went. My resting heart rate data was especially useful for this, because it seemed somewhat independent of my subjective feeling. It made the healing visible.

Finally, the process of logging everyday also reminded me if I had maintained my focus, and reminded me to care about recovery even the midst of my sadness and loss.

The structured phase of my recovery is now complete. In my last physical therapy session, two people played three ball catch with me while I stood one legged on a half exercise ball. It wasn’t pretty, but it sure was fun.