QS Primer: Spaced Repetition and Learning

Gary Wolf

June 22, 2012

Many people think the Quantified Self mostly involves physical metrics: heart rate, sleep, diet, etc. but what about what goes on in our brains? Can we quantify that? There have been several inspiring Quantified Self talks about tracking learning and memory. This post will collect all of them into one place, along with good resources for further exploration.

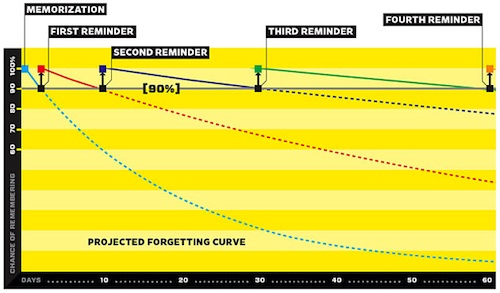

Memorization is only a small part of learning, but it in many circumstances it is unavoidable. There is an ideal moment to practice what you want to memorize. Practice too soon and you waste your time. Practice too late and you’ve forgotten the material and have to relearn it. The right time to practice is just at the moment you’re about to forget. If you are using a computer to practice, a spaced repetition program can predict when you are likely to forget an item, and schedule it on the right day.

In this graph, you can see how successive reminders change the shape of the forgetting curve, a pattern in our mental life that was first discovered by one of the great modern self-trackers, Hermann Ebbinghaus. With each well-timed practice, you extend the time before your next practice. Spaced repetition software tracks your practice history, and schedules each review at the right time.

Convenient tools to take advantage of fast memorization techniques have been around since Piotr Wozniak began developing his Supermemo software in the early 1980s. (I wrote a profile of Wozniak for Wired in 2008, which is cited in some of these talks.) Many of us in the Quantified Self use spaced repetition. We’ve put together this page to list resources, share experiences, and invite comments and questions. We hope you find it useful. If you do, please contribute some knowledge or questions to the comments.

Below you’ll find the following sections:

- Learning Chinese with Spaced Repetition

- Winning Jeopardy with Spaced Repetition

- Using Spaced Repetition to Build General Knowledge and Curiosity

- Using Spaced Repetition as a Cognitive Assay

- The Value and Limits of “Well-Formulated Knowledge” (i.e. good flashcards)

- List of Spaced Repetition Software Tools

- Academic References on Spaced Repetition

Learning Chinese With Spaced Repetition

Spaced repetition is frequently used to quickly gain vocabulary in a foreign language. In this talk from a 2012 Bay Area QS Show&Tell, Jeremy Howard describes his experience learning Chinese.

Winning Jeopardy With Spaced Repetition

Roger Craig holds the all time record for single day winnings in Jeopardy. In this video, he describes his training method, which included the spaced repetition software Anki.

Using Spaced Repetition to Build General Knowledge and Curiosity

At the Portland Quantified Self Show&Tell, Steven Jonas presented this fascinating talk about using spaced repetition to build general knowledge and stimulate curiosity. He concludes hat the value of memorization is not in the mere knowledge on the cards, but in the establishment of a mental structure upon which new thoughts and knowledge can develop.

Using Spaced Repetition as a Cognitive Assay

Nick Winter is the author of a popular Chinese and Japanese learning program called Skritter, which includes spaced repetition as a key feature. Here are the slides from a Quantified Self Show&Tell talk by Nick in which he discusses how spaced repetition practice can be used as a reliable cognitive assay; that is, a test of how well the brain is functioning. Because spaced repetition practice tends to be of consistent difficulty, patterns in our performance can offer clues about what makes us more or less able to learn. (Nick has some results from these experiments that he promised to share in comments.)

The Value and Limits of “Well-Formulated Knowledge” (i.e. good flashcards)

This is a bit of an advanced topic, but I mention here to stimulate interest and comments; do add your thoughts if you have something interesting on this. Piotr Wozniak has a long section on his web site called Effective learning: Twenty rules of formulating knowledge. There are many tricks here. But note the first rule: Do not learn if you do not understand. He offers the rather hilarious example that it is possible, using Supermemo, to memorize a textbook on German history in German, even if you know no German. Possible, yes, but also stupid and useless. Spaced repetition helps directly with one facet of learning only: memorization. Learning involves other things too. Steven Jonas talk about the value of “trivial” information demonstrates; we’re still discovering different ways to make spaced repetition valuable in the larger context of learning. We’re interested in your experiences.

Animated Simulation of Learning with Spaced Repetition

Andrew Marrero created a simulation of the effect of memorizing using spaced repetition vs. other kinds of flashcard practice. It is a great visual explanation of the power of this technique.

[Found via the spaced repetition resource page at gwern.net]

Spaced Repetition Software Tools in Common Use

This is a shorter list than you will see in the Wikipedia entry on spaced repetition. That’s because it includes only tools that we know to be in use by people who have mentioned it to us. If you are using something actively, and are willing to share your experience, please let us know.

- Anki – Widely used and in active development. Open source. Desktop and Android versions are free. iPhone version is $24.99

- Mnemosyne – Also open source; runs on Windows/Mac OS, with card review possible on Android and Blackberry mobiles. All versions are free.

- Skritter – Chinese and Japanese only. Looks great and is written by a good QS friend (see Nick Winter’s talk, above), but I don’t learn these languages so I await your reports. Subscription: $9.95/month.

- SuperMemo – The original; still widely used. There are some licensed versions on other platforms, but the main line of development is Windows only. ($60)

Academic References on Spaced Repetition

A good place to begin is with Piotr Wozniak’s General principles of SuperMemo, which has many links to deeper explanations of his software, experience, and research. Here are some additional sources. (You are welcome to contribute, too. Add references in comments for now, and I’ll go back and incorporate them into this list.) Most of these are readable without specialized knowledge.

- Bahrick, H. P. (1979). Maintenance of knowledge: Questions about memory we forgot to ask. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 108(3), 296.

- Bahrick, H. P. (1984). Semantic memory content in permastore: fifty years of memory for Spanish learned in school. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113(1), 1.

- Bahrick, H. P. (1985). Associationism and the Ebbinghaus legacy. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 11(3), 439.

- Bahrick, H. P., & Phelphs, E. (1987). Retention of Spanish vocabulary over 8 years. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 13(2), 344.

- Bjork, R. A. (2001). Recency and Recovery in Human Memory. In The nature of remembering: Essays in honor of Robert G. Crowder. American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10394-011

- Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1992). A new theory of disuse and an old theory of stimulus fluctuation. From Learning Processes to Cognitive processes: Essays in honor of William K. Estes, 2, 35–67.

- Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2006). Optimizing treatment and instruction: Implications of a new theory of disuse. Memory and society: Psychological perspectives, 116–140.

- Bjork, R., & Richardson-Klavehn, A. (2002). Memory, Long-term. In Encyclopedia of cognitive science (Vol. 2, pp. 1096–1105). London: Nature Publishing.

- Dudukovic, N. M., & Wagner, A. D. (2006). Attending to Remember and Remembering to Attend. Neuron, 49(6), 784–787. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.008

- Grote, M. G. (1995). The Effect of Massed Versus Spaced Practice on Retention and Problem-Solving in High School Physics. Ohio Journal of Science, 95(3), 243–247.

- Landauer, T., & Bjork, R. (1978). Optimal Rehearsal Patterns and Name Learning. In M. Brunebert, P. Morris, & R. Sykes (Eds.), Practical Aspects of Memory (pp. 625–632). London: Academic Press.

- Mozer, M. C., Howe, M., & Pashler, H. (2004). Using testing to enhance learning: A comparison of two hypotheses. Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 975–980.

- Pyle, W. (1913). Economical learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 4(3), 148.

- Traxel, W. (1985). Hermann Ebbinghaus: In memoriam. History of Psychology Newsletter, 17, 37–41.

- Wagner, A. D., & Davachi, L. (2001). Cognitive neuroscience: forgetting of things past. Current Biology, 11(23), R964–R967.