Family Trajectories: An Interview with Stephen Cartwright

Gary Wolf

April 5, 2019

Stephen Cartwright has been tracking his location by the minute for more than twenty years, using the detailed records as material for artworks that embody biographical time with a materiality through which invisible forces can be seen. The patterns of movement that we normally think of as being the result of linear causes – you decide to go someplace, and then you go – appear as trails through a medium that exerts its own force. In his latest work, he plots the “tectonic shifts” patterning the lives of six siblings divided by age into two groups born about a decade apart.

Gary: Tell me about your latest work.

Stephen: For many years I’ve been paying attention to how the trajectories of my family have influenced my own trajectory through space and time. I did that by asking my family members where they were, where they traveled, what their calendar looked like. I started with my immediate family, but I also have three half-siblings that I didn’t get to know until I was much older in life. I’ve met them just a few times each. It was a big step for me, but I contacted them to see if they would like to participate in collaboratively making a sculpture.

Gary: How did it happen that you are just getting to know them?

Stephen: I grew up with my two sisters, but my Dad also has three kids from a previous marriage. My three older half-siblings are a little more than 10 years older than me. They didn’t have much contact with my dad, so my two sisters and I learned about them when we were tweens. We didn’t think we would ever get to see them. But, the youngest of the older half-siblings reached out to my dad some years ago, probably because he was going through a divorce and was thinking about families and fathers. That eventually led to us all meeting each other. At my dad’s 80th birthday in 2017, we were all in a room at the same time for the first time.

Gary: You didn’t have any contact growing up?

Stephen: No, we didn’t even meet until we were all adults. My grandmother maintained a relationship with both sets of grandchildren. In a certain way we coexisted, we were in the same space at the same time, because there were pictures of all of us around her house. I think the pictures got flipped around depending on which set of grandkids were there. It sounds a bit extreme, but I think many families have some unusual arrangements that come to pass through whatever circumstances.

Gary: This kind of reality of a family isn’t easily represented using, say, family pictures, which require that everybody be in the same place at the same time.

Stephen: In order for us to be there first-hand for another person’s experience, we need east and west and north and south and time to all line up. And if just one of those axes diverge, then you have two different experiences.

Gary: How do you work with the data?

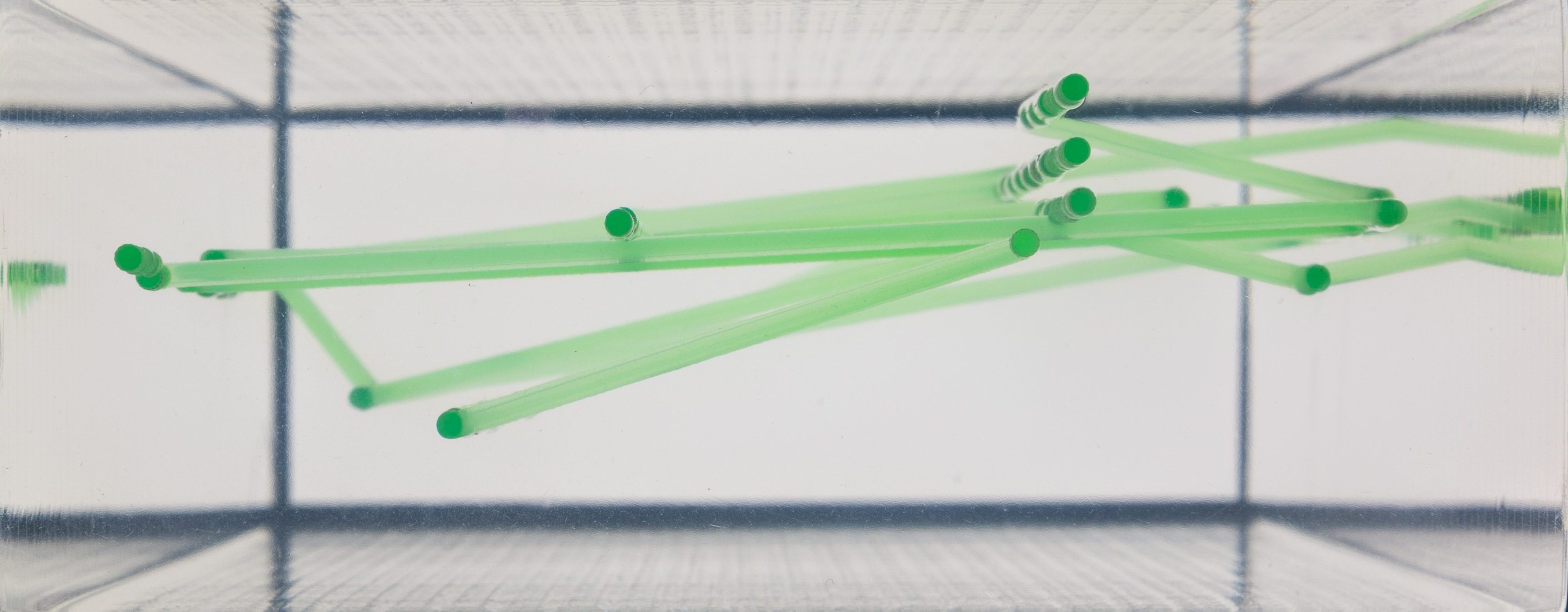

Stephen: The sibling sculpture covers 60 years, so I cut 60 rectangles out of plexiglass and drill holes where each sibling was during that year. If they move, I gouge a line across the plexiglass from where they started to where they ended up that year. When I glue those 60 pieces together, the holes drilled for people staying still make vertical lines moving through the piece, and the lines made by gouging become horizontal lines. The main body of the piece is transparent plexiglass, and the drill holes and the gouges are filled with a colored resin so you can see those lines in the material.

Gary: In your earlier work, which you’ve showed at the QS conference, the lines look like they are being pushed around by some kind of wind or current.

Stephen: I think about this piece more in terms of gravity and gravitational pull. You are moving through space and another gravitational body comes near you and you may get bound up and start orbiting around each other very closely. Or, you may sort of sling off one another. Suddenly you’re repelled away. As I move through my own life on my trajectory, making my line through space, there are other people occupying other spaces that may influence me. With so many trajectories there is always the possibility of interconnections and entanglements but you can’t really experience another person’s reality. I occupy only this tiny little fissure through the medium of space and time.

Gary: How did you gather the data?

Stephen: I have hourly location data for myself for the last 20 years. I have daily location data from my immediate family and my wife for 10 years. Then, using passports and photographs we were able to put together a three-dimensional map of our movements by year since birth.

Gary: Is there a family pattern? For instance, it’s common for families to scatter as kids grow up.

Stephen: In this sculpture you can see kind of two kinds of things happening. My dad was born in 1937. In 1937 a vacation was going camping on a lake 50 miles away. As we move into the modern age travel gets easier and makes the maps more complex and diverse. But the project creates an interesting visualization of family dynamics. My line and the lines of my sisters, my mom and my dad are totally continuous for the first 13 years of our lives. Then, when we move into high school and college things get more interesting and people are going in every direction all the time. So, you see both the transition to the modern age and also the life-cycle of a family. We’re together and then apart, and maybe be more together towards the end.

Gary: How did your siblings react to your invitation to make this together?

Stephen: I was pretty nervous at first because I didn’t know if they would be touched or offended. But I believe it was very positive for them, because it started a conversation between the six siblings that hadn’t happened before. People were remembering times and places collectively and separately.

Gary: Are you finished with this project?

Stephen: Well, this physical sculpture with the siblings, the object is finished, but I hope to keep track of my siblings from now on. And when they move I can update my drawings and possibly make a new sculpture about that. I’m now working on an online project that allows anyone to input their location data and see it in this same kind of way, mapping with people they know, or people who were born at the same time as them. My goal is for other people to be able to experience this kind of three-dimensional laying out of a life.

Gary: To generate a physical object?

Stephen: The initial phase would be to get the dynamics of a map that mimics the 3D thing on a 2D screen. But from that information I would like to generate objects too.

Gary: It’s interesting that you’re doing this as that in a way it’s hyper-legible, but only to the person whose experience it represents. There are no labels on it, there are no pictures, there is no text.

Stephen: For me these are artworks first. They aren’t necessarily data visualizations, and so I have the liberty to treat them as sculptures. In contrast, the digital project will allow users to hover over a line and read whose line it is and the location at that point. I think people will need those clues in order to be able to wrap their head around what they’re seeing. To me there are interesting questions there, interesting debates: How much can you change what the data means by the way you look at it?