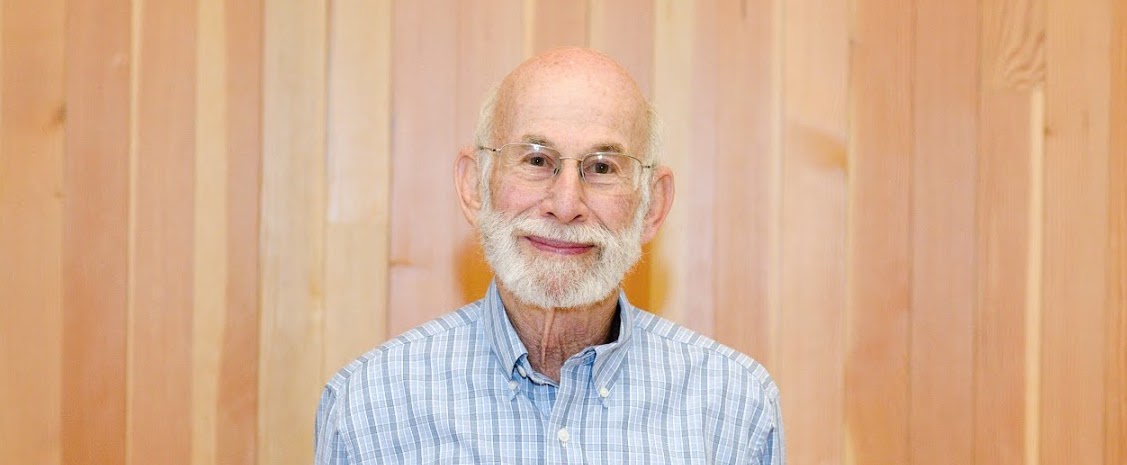

Allen Neuringer’s Decades of Self-Experimentation

Photo by Kim Miller.

Steven Jonas

January 1, 2023

Allen Neuringer’s reason to self-experiment was simple: How could he not apply science to his own behaviors and see what he can learn?

Trained at Columbia College and Harvard University, where he studied with BF Skinner, Allen’s field is the experimental analysis of behavior. As a professor of psychology at Reed College (now professor emeritus), he noticed that few behavioral psychologists studied themselves in the same way they studied their animal subjects. Allen suspected that if he applied the scientific method to his own life, he would learn and be able to help others more.

Could the Heart Do What the Mind Wants?

Allen’s self-experiments began in the early 1970’s. He asked himself silly questions and tried to answer them. There were many failures, but that was okay. Failures in science are important. An early experiment that he regarded as a failure was the attempt to answer a question: If he could manually take over his breathing which is otherwise an automatic process, could he exert manual control over his heart rate as well? With breathing rate, he had feedback: it’s easy to tell whether breathing is fast or slow. What if he had feedback about his heart rate? Could he exert influence over it just as he could influence his breathing?

He used a stethoscope to get immediate feedback from his heart, and after wearing it for four days he discovered that, in a way, he could control his heart rate: Quick breaths would increase his heart rate, while holding his breath caused it to slow down. But he considered this result to be a failure, since he was looking for direct control of heart rate, rather than indirect control via breathing.

Another of his early experiments involved questioning why we sleep on a flat surface. Is it just a force of habit? What happens if we are at an angle? Getting buy in from his wife Martha, he used plywood and some bricks to prop up one side of the bed. First, they slept with their heads elevated and found they slid off the bed. With their feet elevated, Allen found that he woke up with a headache. These results were not surprising, but they gave him confidence that he wasn’t sleeping flat due to habit alone. (There are some people who argue that sleeping at an incline improves health. Why not conduct your own test?)

Why Confirmation Bias Is Not an Issue

Allen notes that failures are important because they demonstrate that the experimenter’s expectations did not determine the result. Self-experiment is not merely an excuse to practice wishful thinking or to demonstrate the power of “confirmation bias.” There may be a couple reasons why this is so. For one, the experimenter has an incentive to get a true result. If it really works, we’ll benefit from it. And, there is no incentive to fake a result. There’s no promotion or tenure waiting if the experimenter fudges a result to make it look positive.

A(B) Method for Self-Experimentation

Allen followed a classic model for his experimentation. He posed questions and observed phenomena and thought of possible explanations. Then he would devise an experiment to test his explanation. His experiments usually followed an AB model. He would do activity A for a set period of time (a day, perhaps more), followed by a B period without the intervention. He would repeat this interval, ABABAB, as many times as needed.

He notes that his methods are primarily experimental, befitting his professional background, while most in the Quantified Self community are observational. It’s possible to bridge the two, he notes, citing a former student of his, the late Seth Roberts, a prominent contributor to the early Quantified Self community. Seth monitored certain aspects of himself (mental acuity, for example) over long periods of time. When the results fluctuated unexpectedly, he hypothesized a few reasons why and switched from an observational mode to an experimental mode to test those ideas. Seth credited this method for helping himself generate more ideas than he otherwise would.

Generating New Ideas

Allen had his own method for generating ideas. While a grad student, he went on walks through the basement hallways of Harvard’s Memorial Hall, often passing Nobel Prize winner George von Bekezy, perambulating in the opposite direction. One day, von Bekezy said to Allen, “You walk, yeah?” in a heavy Hungarian accent. Allen nodded. “Good ideas come from walking.” Allen noticed that his ideas didn’t just come in hallways, but on long hikes as well. Movement seemed to generate ideas, but it could also go in the other direction. He noticed that if a good idea popped in his head while working at a desk, it would prompt him to jump up from his seat and pace back and forth.

This Brain Moves

Allen proceeded to test the effects of movement on his cognitive abilities. He tested memory at first. He had flashcards with faces on one side and names on the other. His A condition would be to run two miles or swim 20 laps and then review 20 of the cards recording how many he got right. The B condition would be to spend the same amount of time working at his desk before reviewing the cards. The effect was clear. His ability to memorize was better after activity.

But how does one test idea generation? Allen’s method was to spend 15 minutes moving around in a “quasi-dance” manner and noted any ideas he had on a notecard, writing the date and the condition on the back side, in this case, “move”. He then compared those cards to ones generated during a 15 minute period sitting at a desk.

He repeated these AB intervals over the course of weeks, accumulating piles of cards. Months later he went through the cards and evaluated the quality of the ideas, looking at whether or not they were good and how creative they were. He didn’t know which conditions they were, since “sit” and “move” were written on the back side. He calculated the number of subjectively judged “good” ideas for each condition. Again, he noticed there were clear differences. Movement helped.

Movement also helped with reading. Allen rigged a book holder out of an old backpack and through his testing found out that he surprisingly reads faster while moving and retains more. But was moving always better? Allen looked at his problem solving abilities in the move and sit conditions, using a similar method that he used for testing idea generation. He found that moving tended to make problem solving easier, with one significant exception: problems involving mathematical reasoning were more difficult to do while moving.

If A Then B

Allen also looked at how he could apply behavioral concepts to his life, like contingencies. A contigency is the relationship between two events, one being a consequent of another. It’s a simple model of “If A then B”.

Some things were difficult for Allen and Martha to do, even though they wanted to do them. Martha wanted to dance more, Allen wanted to write. So they agreed to a simple contingency: If she dances for 15 minutes and Allen fails to write, then he cooks and does the dishes. Vice versa if he writes and she doesn’t dance. If they both do their thing or fail to do their thing, they share as normal. Even though this wasn’t a terribly aversive contingency, Allen reports that it worked like magic on their behavior. Today, there are apps that now help you to set up contingencies, such as Beeminder. However, Allen wonders if his and Martha’s use of interpersonal contingencies has a more powerful effect. Something worth testing!

Learn More

To learn more about Allen, read his paper from 1981 advocating for self-experiment as a method of discovery. You can also watch his Quantified Self talk about his career, historical self-experimenters, and what his students have learned from their own self-experiments.