Exploring the Future of Mood Tracking (Get Your Mood On: Final Part)

Alexandra Carmichael

February 14, 2013

Welcome to the sixth and final part of the QS book on mood tracking that Robin Barooah and I wrote. This chapter has some thoughts on what the future of mood tracking might look like. Thanks for being on this journey with us!

—

At this point, you should have a good understanding of the nuances and methods of tracking mood. You could stop reading here and be well-versed and ready to go. If you want a peek into some possible new ways to track mood in future, read on.

Passive Body Position and Movement

What if your mood could be measured without you having to do anything or enter any data? Would this be helpful, or is the act of reflecting on your mood the useful part? We mentioned a few existing examples earlier, like tracking what music you listen to, and your voice patterns. Here are a few other efforts happening:

A sensor called LUMOback can be stuck on your back to detect your posture throughout the day and report to you via your smartphone if you are slouching. They don’t specifically talk about mood tracking as an application for this, but posture is a known sign of mood. When we’re depressed, we don’t stand up tall.

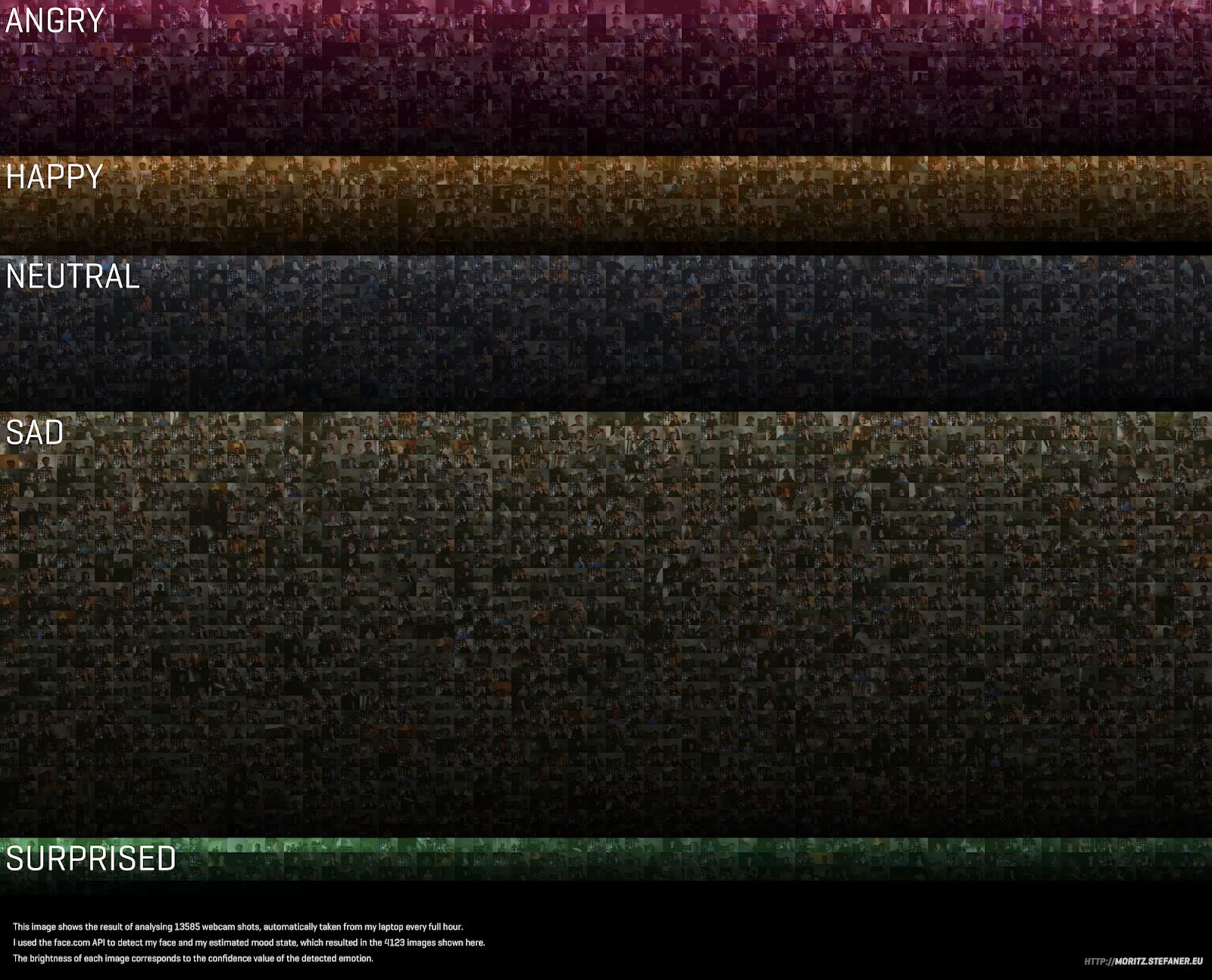

Other experimental ways to passively capture mood include keystroke logging, which involves detecting how quickly and actively you are typing on your keyboard, and using your webcam to take random pictures or continuous video of yourself while you’re at your computer. Moritz Stefaner did a project in which he automated hourly webcam pictures of himself. He then had 13585 of the pictures analyzed for mood, with the following result.

A lot of his “sad” photos are really just him concentrating, mislabeled as sadness. but Moritz’s project shows the potential power of the cheap, universally available webcam as a passive mood tracking device.

Reverse Mood Tracking

A fascinating way of using mood tracking in a clinical setting has been pioneered by Dr. Alan Greene. He was kind enough to share his story with us here:

“Most mood trackers I know tend to notice, record, and track their moods in order to gain insights about themselves. I’ve come to also do the reverse: track my moods to gain insight about others.

It all started when I walked through a door.

That morning in my office the waiting room was jammed. The first few patients I saw were delightful children I already knew, who had come in with minor complaints. I sped through the morning, pausing to smile at each child, but hurrying to keep on schedule.

The next chart in my in-box had an unfamiliar name. I stepped through the door into the exam room and saw a nine-year-old boy. Large clefts marred the middle of his face. Although a scar suggested that his cleft lip had been repaired, he was still left without nose or eyes. He did wear glass eyes in an attempt to make his visage more presentable.

“You must be Stephen,” I smiled, “I’m Dr. Greene.” I reached forward, took his hand in mine, and shook it warmly. The hand at the end of his shortened arm was missing three fingers.

I recognized Stephen’s condition as the Amniotic Bands Sequence, which affects only about one in 25,000 otherwise normal children. When Stephen was still waiting to be born, his forming face fused to the membrane lining of the amniotic sac. Normal development arrested, resulting in the large clefts in his mid-face. Part of the amniotic membrane ruptured, and the sac that was supposed to protect him, instead entangled his developing limbs in shriveled, fibrous, amniotic strands. Decreased circulation to the limbs caused multiple deformities and amputations. Normal intellect and normal emotions were framed in a twisted, blind body.

“I’m glad this sweet boy will never see his own face,” I thought. Looking through his chart, I looked up to ask a question, and saw tears making their way down the crevices of Stephen’s face. Mild surprise that his tear ducts functioned gave way to genuine concern over what had made him cry. I placed my hand gently on his shoulder and asked what had provoked his tears.

“I’m just happy, Dr. Greene… you smiled at me!”

This boy with no eyes had felt my smile, just as he had felt the averted gaze of many passers-by. And the smile had touched him deeply.

But how had he known?

A few years earlier, modern neuroscientists at one of the oldest universities in the world had implanted electrodes into the brain of a monkey to learn what cells would fire when a monkey brought food to the mouth. The experiment was going well and the results were consistent.

On a hot afternoon, a graduate student walked through the door of the lab carrying an ice cream cone. When the student brought the ice cream to his mouth, the food-to-mouth cells in the monkey’s brain fired even though the monkey hadn’t moved. Later, the team found that watching or even hearing food being opened or eaten produced the same results.

This gave rise to the theory of mirror neurons: neurons in our brains that fire in response to others’ actions or even emotions – as if they were our own. The theory is far from perfect, but certain areas of the brain, including the anterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex and inferior frontal cortex light up when people experience a strong emotion – or sense someone else having one.

Thus started my experiment with Reverse Mood Tracking. Before I would walk into a room, I would pause briefly outside the exam room door and note my current mood. Then, after walking through the door I would pause and note whether my mood had changed. My hypothesis? That the new mood would reflect, at least in part, what was going on with those in the room. So I would make a probing statement or question to learn if I were correct, and use the feedback to hone my perceptions.

Door = trigger

Mood check A

Enter room

Mood check B

Note difference and form a hypothesis

Test hypothesis

Adjust

Sometimes I would walk into a room and notice feeling more tired or overwhelmed, so I would test, “Isn’t it exhausting to be a parent sometimes?”

Often the answer would affirm my hypothesis and quickly establish an empathic connection, “My baby won’t let me sleep longer than three hours!”

Sometimes my mood change was an accurate mirror, but my hypothesis was wrong, “I’m exhausted, but’s it’s not the kids – it’s my husband!” This still quickly establishes rapport.

Occasionally, I’m completely wrong, “I’m not tired, I just feel dead inside.” But by addressing mood, we can still get to the issue of depression more surely than otherwise.

Whether the subtle mood change is toward fear (“Often when parents find a lump, they’re scared about cancer.”), or guilt (“Are you concerned someone may have been touching Sally inappropriately?”) or joy (“Isn’t 3 years old an amazing age?), reverse mood tracking is the quickest way I’ve found to connect and to get to the heart of the matter, the issue behind the reason stated on the intake form.

I’ve learned that I get better at this with practice, that the technique is useful beyond exam room doors (though with personal and business doors I need to be more aware of any previous feelings of my own about the people in the room). And I’ve gained a new appreciation of how connected we are. We affect each other in ways we are just beginning to discover.

As I stood in the exam room with Stephen, it struck me as profound that a gift as simple as a smile could be so powerful (smiles light up mirror neurons and we often smile in response).

When we see someone afflicted, whether emotionally or physically, it is easy to turn away. What an important act of humanity to look in the eyes (even if there are none), and see a person, not just a problem.

But it’s not just the disabled who need reassurance. In our mobile society, our moorings both to place and to people have been loosened. We are adrift in a rolling sea of humanity. By looking with fresh warmth and compassion at the people who surround us each day, we create new connections. By seeing beyond surface appearances to the unique miracle of each individual, we are all buoyed.

As I stood in the exam room with Stephen, the two of us beaming at each other, I was so glad I had opened that door.”

Biometrics

What if there were a continuous way to measure levels of things like cortisol in your blood or saliva, as a measure of your live stress level? What if a galvanic skin response (GSR) sensor that measures your sweat could broadcast your stress level to people around you? One couple did this for their wedding day, calling it “Project Cold Feet.” They hooked up GSR sensors from the bride’s wedding ring to LED lights on her bouquet. If she got excited or stressed, the lights would turn white. If she was calm, they would be blue.

This brings up the question of how widely people will want to broadcast their mood. Will it be a part of every Facebook or Path status update to include a quick emoji based on your passively calculated mood state? There could be a gradient that emerges in mood sharing, from “mood nudists” who broadcast every mood publicly, to “mood monks” who prefer to keep things to themselves, to “mood ignorers” who don’t even want to know anything themselves about their emotions.

Live neurotransmitter levels

On a more speculative note, what if measuring neurotransmitter levels in your brain could give you a clue into how your mood changes over time? Enter the Lövheim cube of emotion. This model maps out eight emotions that form the corners of a cube, where the axes of the cube are levels of norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin.

For example, according to this cube, if you have high serotonin and high noradrenaline levels, you would be feeling surprise, and if you have high dopamine and high serotonin, you would be feeling joy. Low levels of all three, and you’re stuck in shame and humiliation.

An issue with this model is how to accurately measure neurotransmitters. Assuming that this measurement can one day be done reliably and continuously, tracking your noradrenaline, dopamine, and serotonin levels could be an interesting way to record your mood. It would also be interesting to see if there were any cases in which the levels predicted one emotion, say disgust, but you felt something different.

Brain waves

What if looking at electrical activity in your brain could influence your mood? Alan Bachers is working on a product called NeurOptimal that is basically an EEG (electroencephalography) sensor combined with visualizations for neurofeedback. When you are wired up to this system, you can see how your brain is responding to your current environment and emotional state. If you discover that you are stressed, you can concentrate on changing the visualization to a calmer one.

The system is claimed to be able to facilitate entering into meditative or desirable mental states, and possibly to help people on medication for ADHD and other mental health conditions to learn to function without medication.

Life doula

While she was at the Institute for the Future, Alex had the following idea for a “life doula,” basically an artificial intelligence that would take care of us depending on our moods and other health data, give us reminders for self-care, and generally be a supportive presence:

“Adaptive encouragement: From self-quantifiers to life doulas

Imagine a digital advisor that interprets your raw health data and offers continuous support along with interactive data visualization and recommendations for changing—and maintaining—daily routines or medications.

Embodied in intelligent programs, mobile devices, and the cloud, a life doula (like a birth doula) will remind us of our goals in moments of weakness. It will offer suggestions and encouragement in context to help us make healthy choices.

This kind of adaptive, personalized support will improve chronic illness management with automated diet tracking, in-home blood marker monitoring, and real-time analysis of genetic, metabolic, and protein data.”

Intel researcher Margie Morris has already started experimenting with this kind of thing. She wired people up with electrocardiogram (ECG) sensors to monitor their heart rate variability (HRV), which is basically the changing amount of time between heartbeats. This is a general indicator of health as well as stress levels.

When the sensors detected a change in HRV that indicated stress, they would cue a smartphone app to show breathing visualizations and Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT)-based suggestions. The study participants enjoyed the system and found it helpful, suggesting that further research into this idea is warranted.

Mood Culture of the Future

As more people turn their attention towards mood and emotion, how will this shape our culture? Will we live in a future where different neurological conditions and mood states are accepted just as different skin colors and sexual orientations are currently accepted? Will people become more self-aware, overcome their fear of vulnerability, and tune into the nuances of their emotions?

Or will we live with the mysterious possibility in which moods are never mapped and understood fully, because they are a reflection of our ever changing world? Are moods like colors – to be gradually distinguished and named? Or are they part of an ever changing pattern of growth of which we are all a part?

We as authors don’t have the answers to these questions, and perhaps in the new world that is emerging, answers from any author are of less importance than the answers you can find for yourself using the tools of self-discovery that are the surprising fruits of the digital revolution. Best wishes on your mood tracking journey!

Alex Carmichael – @accarmichael

Robin Barooah – @rbarooah

References:

http://www.lumoback.com

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lövheim_cube_of_emotion

A new three-dimensional model for emotions and monoamine neurotransmitters. H. Lövheim / Medical Hypotheses 78 (2012) 341–348

http://news.cnet.com/8301-17938_105-10437624-1.html

http://moritz.stefaner.eu

http://geekphysical.com/coldfeet_readmore.php

http://quantifiedself.com/2012/01/alan-bachers-on-optimal-neurology/

http://www.zengar.com

http://www.iftf.org/node/4078

http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpls/abs_all.jsp?arnumber=4814939&tag=1