QS Guide: Testing Food with Blood Glucose

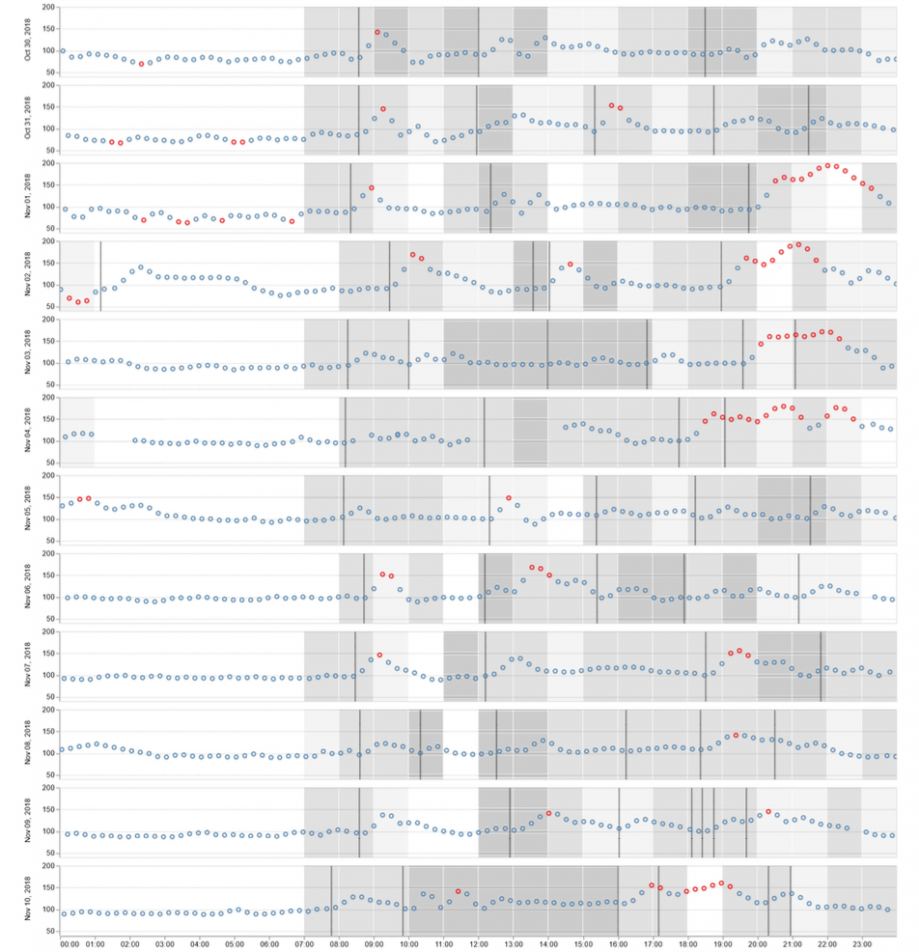

Twelve days of blood sugar data overlaid with steps (the shaded areas). Image: Eric Jain

Steven Jonas

September 19, 2019

*Resources and references linked to in the text are repeated as an organized list at the end of this guide.*

As we’ve covered, people with diabetes are pioneers in the Quantified Self community. Self-tracking has been a necessity for controlling their blood sugar. This need for better understanding and control has pushed them far beyond what was available from available medical devices. As technology is developed to meet their needs (some of it coming from the diabetes community itself), we are starting to see more people in the QS community who are using glucometers and continuous glucose monitors even though they don’t have diabetes.

There is a range of things that can be investigated with the measurement of blood sugar. Some people are learning how the stress of a new job impacts their physiology. Some looked at whether certain supplements impacted their fasting blood glucose reading. Others are finding blood sugar measurements to be useful for understanding their response to specific foods. This article will focus on that last one.

What is this all about? Recent studies from Eran Elinav and Eran Segal, researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, found that people’s response to food is highly variable. Conventional wisdom about which foods are “good” or “bad” don’t seem to hold up when you look at individual cases. In one study, they looked at how people’s blood sugar responded to eating white bread and the supposedly healthier option of artisanal sourdough bread. Surprisingly, an equal number of people responded positively to white bread and negatively to the artisanal sourdough bread as the reverse. That a population can have such wildly different responses to a food suggests that universal dietary guidelines may be of limited use. (This animated video, produced by the journal that published the study, is a good overview of the research)

This may shed light on how diets with antithetical tenets both seem to perform well when tested. It may be that the person on the internet who is advocating for paleo is one of those whose blood sugar levels respond well to the majority of the foods on that diet. Still, the person may not respond well to every item on paleo’s “good” food list. Similarly, there may be items on the “bad” list that their system tolerates just fine. Currently, the only reliable way to find out is to test it with one’s own blood sugar readings.

Why blood sugar?

Why would blood glucose (blood sugar and blood glucose are synonymous and I’ll be using them interchangeably in this guide) be a meaningful way to test whether you should eat a certain food? The researchers argue that high blood sugar levels are linked to a myriad of diet-related diseases, such as the epidemic levels of prediabetes and type-II diabetes in most well-off countries. Reducing the frequency of a person’s glucose spikes by managing the food they eat will likely prevent various manifestations of metabolic

Measuring post-meal blood glucose is also practical. Blood sugar levels respond quickly to foods and is easier to test at home than other measurements.

Considering how similar human DNA is among individuals, how could the responses to the same food be so varied, to the point of being contradictory? The current theory is that the biggest factor is people’s gut microbiome. Depending on the specific bacteria in a person’s intestinal tract, the way that food is processed can be much different.

There are companies that are looking to provide people a nutrition plan based on their microbiome and other personal information. Richard Sprague from the Seattle QS community tried two of the companies and received contradicting recommendations. Until the predictions become more reliable, the surest way to build your personalized nutrition is through your own testing, which the rest of this article will walk you through.

How to Test Your Food

There are two primary ways to measure your blood sugar: a finger-prick glucometer or continuous glucose monitor. The instructions here are based on how people who shared their projects to the QS community have tested themselves.

Tools

Finger-Prick Glucometer

In order to start testing your blood sugar, you’ll need:

- glucometer

- testing strips

- lancets

- a place to record your data

A glucometer can be purchased online in a local drugstore or online for under $30. I suggest buying a model that will store and export your readings. Testing strips can run about $40 for 100 strips. And 100 lancets can be bought for under $10.

The packaging should have instructions for basic operation of the device. This page has detailed instructions, as well. It’s important to wash your hands before taking a measurement. It’s possible for sugar on your skin to get picked up on the testing trip (e.g. after peeling an orange). You’ll want to validate your device by testing your blood three times in a row and seeing if the results are within a 20 mg/dL (1.1 mmol/L for countries that use that measurement) range, which is a normal level of deviation for home devices (check out our guide for validating your device). If it’s outside that range, you may have a faulty device and should exchange it.

You will need to record your blood sugar values, times, and food. The simplest way is to use a small notebook. In terms of apps, you could try one from this list or use a simple database app (I currently use this one) where you can manually create your own fields. Some glucometers will store and export the data, but it may be a clunky process. Eric Jain of the QS Seattle community took pictures of his food with his phone and used the timestamps.

Continuous Glucose Monitor

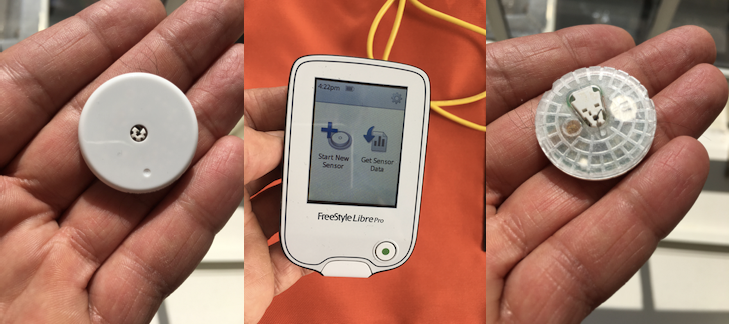

A continuous glucose monitor (CGM) makes it easier to get a full picture of your blood sugar because it is attached to the body and takes continual readings. There are a few CGMs on the market, but so far, most projects presented to the QS community have used the FreeStyle Libre. Since this guide is based on the practical knowledge shared in those projects, we are going to focus on that model. (Technically the FreeStyle Libre is considered a “flash glucose monitoring system”, but the difference is not necessary to get into for the purpose of this guide.)

To use a FreeStyle Libre, you’ll need:

- FreeStyle Libre reader or phone with an NFC chip and companion app (iOS/android)

- FreeStyle Libre sensor

- a prescription (required in the U.S., but not in the European Union. For other countries, it may require some research to determine whether a prescription is necessary or if the device is even available.)

The FreeStyle Libre works by having a sensor that attaches to your upper arm with a short filament that is inserted under the skin. To get data out of the sensor, you hold up either the FreeStyle Libre reader or a phone with an NFC chip and the companion app (iOS/

The FreeStyle Libre reader costs about $70-$90 dollars. Sensors last for 14 days, costing about $35-$50 dollars each.

This page has instructions for general operation. Note that for calibration, it is suggested that you buy testing strips (the FreeStyle Libre has a reader that allows it to read testing strips like a traditional glucometer). Richard Sprague found that the FreeStyle Libre measurement trailed the glucometer measurement by about ten minutes. This is because the FreeStyle Libre is not measuring blood directly, but the amount of glucose in the interstitial fluid under your skin.

To view your data outside your phone, there is a FreeStyle Libre website and desktop app that can be used. Eric Jain found Tidepool to be more reliable for transferring data and more flexible for tagging meals.

The principles for testing your food with a CGM is the same as the glucometer (details on testing will be covered in the next section). However,

Testing Method

Establish Baseline

The first step is to figure out your fasting blood sugar. This will establish a baseline that will be useful to compare measurements against for the rest of the day.

Next, you want to decide which food to test. You can test food individually or as a meal. First, you’ll probably want to test meals that you normally eat. Afterwards you can try testing food that you think is problematic or if one of your meals had a higher blood sugar response than you would like, you can try variations of that meal. (More on this in the “Things To Try” section.)

Before eating, test your blood sugar. You’ll want it to be within 20 mg/dL (1.1 mmol/L) of your baseline. If it is above that, it most likely means that your blood sugar is still elevated from something that you ate prior. You’ll get a more reliable results if you wait until your blood sugar level is close to baseline.

After establishing that you are near your baseline, note the time that you begin eating and set a timer to test yourself again. The researchers suggest that you test every half hour after you begin eating until you are within 20 mg/dL (1.1 mmol/L) of your baseline. Most often it won’t be more than two hours. If you are using a CGM, it’s not necessary to do these spot checks, but you’ll still need to note the time that you began eating and what the food being tested is.

Determining whether a food or meal is “good” or “bad”

It would be nice if there was a simple rule to evaluate your results, such as, avoid foods that show a blood sugar levels of 60 mg/dL (3.3 mmol/L) above your baseline at the one hour mark. However, the researchers note that there is no established guidance for an appropriate post-meal glucose response.

Their suggestion is to test enough foods or meals so that you build a sense of your normal response curve. This includes the length of time it takes you to get back to within 20 mg/dL (1.1 mmol/L) of your baseline, as well as, the magnitude of the initial spike. Any food above your normal values (either the spike or the “elevated” duration) would then go on the “bad” list. One general guideline out there, from the American Diabetes Association, is that a reading of less than 140 mg/dL (7.7 mmol/L) at the two hour mark is normal for people without diabetes.

Unless you get an odd result, you should only have to test a type of food once. From what we’ve seen, both from the community and from the research, the blood sugar response does not vary significantly when testing a type of food multiple times. Still, it’s good to keep in mind that other factors can affect your post-eating glucose response. People have noticed that walking after eating and eating within an hour of strenuous exercise keeps blood sugar spikes in check (and is probably a good practice to follow). At present, not much is known on how changes to your microbiome from changes in your diet will effect your blood glucose response over time.

Variations and Things to Try

If you find that your morning baseline measurement does not vary much day-to-day, you can probably forego the morning measurement after you’ve developed a strong sense of your norm. This can help with the cost of testing strips (obviously not a concern for those with a CGM).

If you are using a glucometer, you may find testing every half hour to be onerous. You may still be eating by the time you are supposed to take a blood sugar reading. If you are finding that this is keeping you from testing at all, consider taking samples only during the hour marks. You won’t get the full picture of the blood sugar response curve, but it should still give you a decent idea of how you are responding to that meal. If you get a high or weird result, you can always test that meal again at half hour intervals.

Jenny Horner, a QS friend in England, had a simple rubric for testing her food. She measured her blood glucose just once, one hour after eating. If the result was less than 125 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L), she categorized it as “okay”. “Avoid” was anything more than a 140 mg/dL (7.7 mmol/L) result and anything in between was labeled an “occasional” food.

One reason why the researchers encourage testing entire meals is that the mixture of ingredients can affect how your blood sugar responds. The research found that, for some, adding a form of fat to their meal will blunt the response of an otherwise blood-sugar spiking food. But for others this had no effect.

Richard Sprague found that the size of the portion was an important factor for how much his blood sugar spiked. So try different combinations of foods and portion sizes to see how it affects the blood sugar response. If you’re deep in the weeds, you could try varying the order in which you eat your food.

Learn From Others

I hope this guide sets you up to start testing food with your blood sugar values. I should note that even though a food may pass the blood sugar test, it’s too early to assume that is the only measurement that matters. It’s going to be odd to encourage common sense after explaining a technique that sometimes defies common sense, but even if you can eat ten chocolate cookies without spiking your blood sugar (as one person found), until we know more, it’s probably better to not make it a daily habit.

The ideas and facts in this article are largely drawn from the popular science book The Personalized Diet, written by the lead researchers of the blood glucose tracking study (plus writer Eve Adamson). Many other observations and techniques are drawn from presentations by Eric Jain, Richard Sprague and Jenny Horner. Thank you for taking the time and energy to share your knowledge. Their presentations and more are given below as resources:

- Eric Jain’s Show&Tell talk and blog post. He used a Freestyle Libre and made some interesting observations on how physical activity affected his readings.

- Richard Sprague’s Show&Tell talk. He used a Freestyle Libre and tested various combinations of foods in a meal to see the glycemic impact.

- Jenny Horner’s blog post. She used a finger-prick glucometer and was surprised to find some very sweet foods did not spike her blood sugar.

- Ben Best’s Show&Tell talk. Ben, using a finger-prick glucometer, tested many foods for many hours.

- Justin Lawler gave a Show&Tell talk on what he learned from wearing the FreeStyle Libre for eight months.

- Bob Troia gave a Show&Tell talk on the effect of Oxaloacetate on his fasting blood glucose.

- The Quantified Ketonian. An interesting blog chronicling a series of personal blood sugar experiments throughout 2019.

- To learn more about the pioneering work by people with diabetes in the QS community and their fight to gain control over their medical devices and data, watch our talks from Dana Lewis and Lane Desborough.

- Simple guide for using a glucometer and a list of blood glucose tracking apps. Ninox is a free, simple-to-use database app that will allow you to make custom fields.

- Instructions for the FreeStyle Libre and some apps for managing the data: iOS / android / desktop / dashboard website / Tidepool.

- QS Guide that walks you through the process of validating your device.

- The paper on developing personalized nutrition through blood sugar and microbiome testing from Eran Elinav and Eran Segal.

- The paper on testing people’s individual response to white vs. sourdough bread from Tal Korem, David Zeevi, Niv Zmora, Avi Levy, Eran Elinav, and Eran Segal.

- A couple easy-to-digest presentations of Elinav and Segal’s research: an animated video and a PDF from a presentation given by Elinav.

- This paper shows no significant difference in weight loss between a low-carb and low-fat diet.

- A pilot study (n=11) finding that eating vegetables and protein before carbohydrates lead to lower post-meal glucose levels for obese people with type-2 diabetes (news release).

If you have questions or if you have started testing your food, let us know in the comments!